Rosalind Franklin 1920-1958

Sixty years ago today, on 25 April 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson published a paper in Nature describing the double helix structure of DNA.

There have been a flurry of excellent articles in the newspapers to commemorate this auspicious anniversary and, (especially) if you are at all unfamiliar with the history and significance of Crick and Watson's discovery, I wholeheartedly recommend Adam Rutherford's piece in today's Guardian.

Adam also relates some details of Rosalind Franklin's story and the way she was belittled by her male colleagues. Franklin's contribution to the unravelling of the structure of DNA was, to some extent, written out of history - a wrong which has only been righted in relatively recent times - and a number of commentators have sought to rescue her reputation (as they see it), set the record straight, and put Rosalind Franklin's name up there where it belongs alongside Watson's and Crick's. (see for example Anne Sayre and Lynne Osman Elkin)

This is not, however, quite the simple female-goody versus male-baddies tale that some modern accounts suggest. Real stories rarely fit tidy narratives.

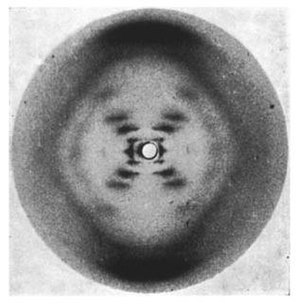

Part of the reason Rosalind Franklin was "written out of history" is simply the fact that she died tragically young and Nobel Prizes are never awarded posthumously. Of course whether she would have received the Prize if she had lived is impossible to say, but even Jim Watson is on record as saying that she should have done. The famous Picture 51 (above) which played a crucial role in the DNA story is often credited to Franklin (see eg wikipedia) and is certainly testament to her skills in this field but it was actually taken[1] by her (male) student Raymond Gosling who (as Adam Rutherford also notes) has been written out of history to an even greater degree than his female supervisor. While Jim Watson is astonishingly patronizing in the pages of The Double Helix : A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA, Francis Crick (as is often noted) is far more generous to Franklin and fully acknowledges the significance of her contribution. He does, however, correctly point out that X-ray crystallography alone could never have revealed the detailed chemical structure of DNA and that the Crick/Watson approach to the problem and Franklin's approach were very much complementary strands (if you'll forgive the pun).

As I say, life is complicated.

But regardless of the complex twists and turns (sorry I can't help myself) of history and science, there is no doubt, however, that Rosalind Franklin was the victim of appalling sexism - and not just from Jim Watson.

Inspired by the various newspaper articles I read today, I dug out my copy of What Mad Pursuit (Crick's autobiographical account of the subject at hand) and reminded myself of one or two things he had to say:

People have discussed the handicap that Rosalind suffered in being both a scientist and a woman. Undoubtedly there were irritating [sic] restrictions - she was not allowed to have coffee in one of the faculty rooms reserved for men only - but these were mainly trivial, or so it seemed to me at the time. (op cit p 68)Well yes, but though I'm a man, I can kind of imagine that a woman might find something like that a teensy bit more than "trivially irritating".

Crick goes on to say:

Feminists have sometimes tried to make out that Rosalind was an early martyr to their cause, but I do not believe the facts support this interpretation. [...] I don't think Rosalind saw herself as a crusader or a pioneer. I think she just wanted to be treated as a serious scientist. (ibid p 69)Now perhaps I've got the wrong end of the chromosome here, but I always thought that a world where women can be treated as serious scientists is exactly the sort of thing those dreadful feminists have always been arguing for.

As a younger man, Crick and Watson's work inspired me to go to university and study genetics. It's hard to imagine they inspired many women to do the same. Let us hope that one legacy of the Rosalind Franklin story is that the next sixty years see many more young women entering science and being taken seriously when they do.

[1] The only reason I know this is again down to the aforementioned Adam Rutherford.